On September 7, 1936, a sad event happened in a concrete cage at the Hobart Zoo in Tasmania.

“Benjamin,” the last known Thylacine (Tasmanian Tiger), died of exposure. He had been locked out of his sleeping quarters during a freezing night. When he died, a 4-million-year-old species vanished from the Earth forever.

Or so we thought.

Fast forward to 2026, and “forever” isn’t what it used to be. Thanks to breakthroughs in CRISPR gene editing and artificial wombs, we are standing on the brink of the first successful “de-extinction.” The Tasmanian Tiger is coming back, and it’s happening faster than anyone predicted.

1. How Do You Resurrect a Ghost?

Bringing an animal back isn’t like Jurassic Park. We don’t have mosquito amber. Instead, scientists are playing a hyper-advanced game of “Cut and Paste.”

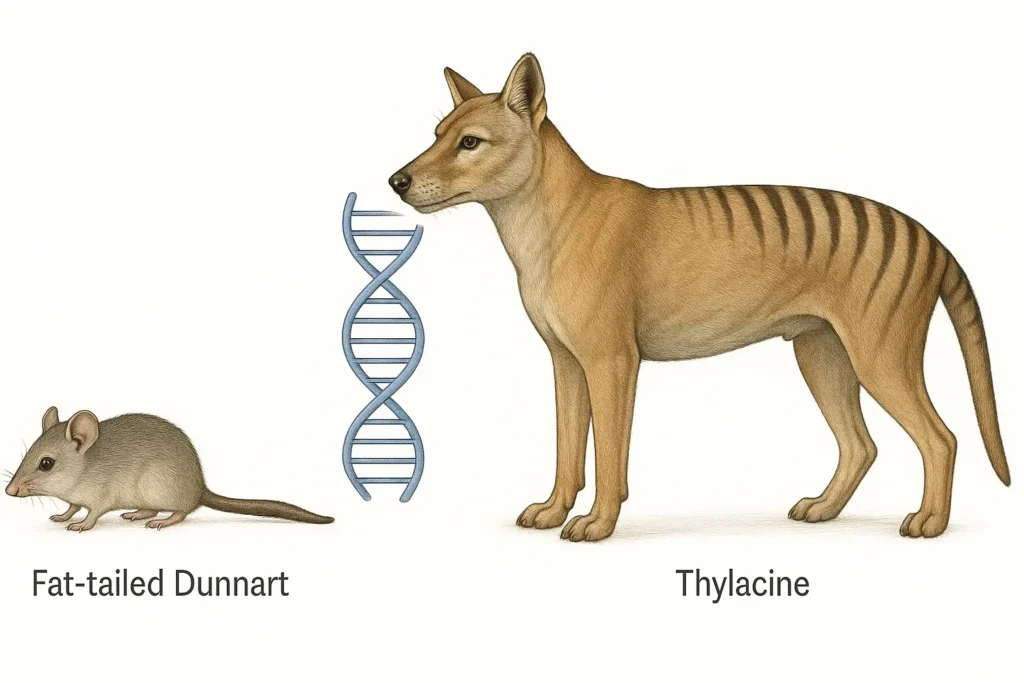

The Thylacine’s closest living relative is a tiny, mouse-like marsupial called the Fat-tailed Dunnart.

- The Blueprint: Scientists have already sequenced the full genome of the Thylacine from museum specimens (preserved in alcohol).

- The Edit: They take the DNA of the living Dunnart and use CRISPR technology to “edit” it, swapping out specific genes to match the Thylacine’s code.

- The Result: A cell that is functionally Thylacine.

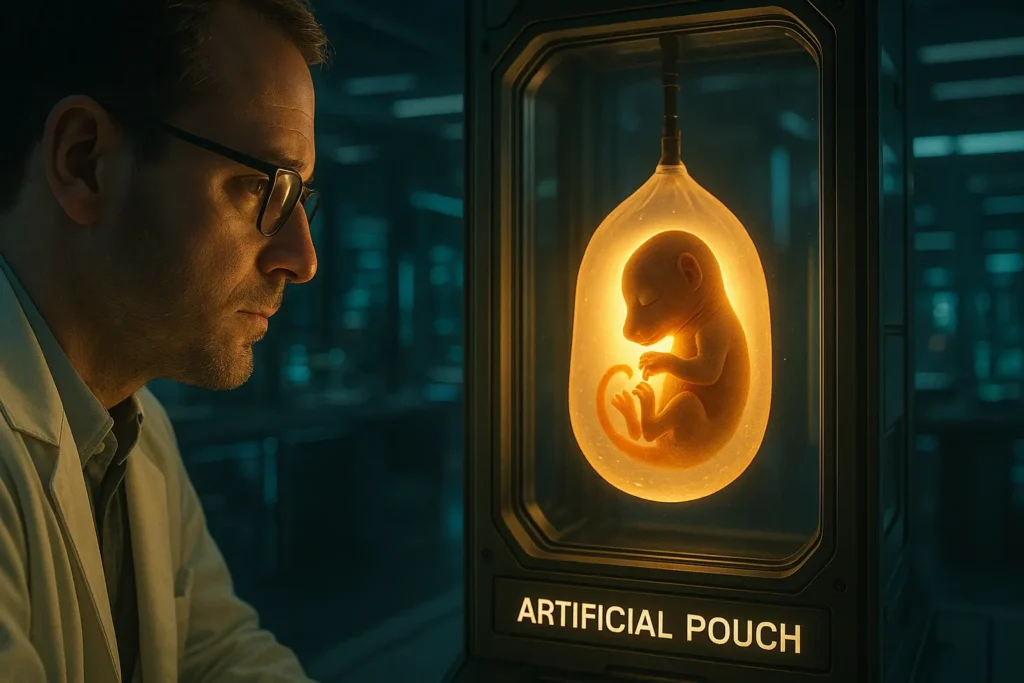

2. The 2026 Milestone: The “Artificial Pouch”

The biggest hurdle has always been: Who gives birth to it?

You can’t put a Thylacine baby (which grows to the size of a dog) inside a Dunnart (which is the size of a mouse).

To solve this, researchers have developed artificial womb technology and are working on an “Artificial Pouch.” In late 2025 and moving into 2026, the goal is to transfer these edited embryos into a surrogate environment for the first time. If successful, we could see the first Thylacine joey born before the decade is out.

3. Why Are We Doing This? (It’s Not Just for Zoos)

Critics call it playing God. Proponents call it “Ecosystem Restoration.”

The Thylacine was a Keystone Predator. When it disappeared, the Tasmanian ecosystem fell out of balance. Invasive species and diseases (like the facial tumor disease killing Tasmanian Devils) ran rampant.

The theory is that bringing back the apex predator will stabilize the environment. It’s not about creating a monster for a theme park; it’s about fixing a hole we tore in nature 90 years ago.

4. The “Frankenstein” Debate

Is it really a Thylacine? Strictly speaking, no. It will be a hybrid—mostly Thylacine DNA, but with some Dunnart scaffolding. It won’t have a mother to teach it how to hunt or behave.

Ethicists argue: Are we creating a lonely animal that has no place in the modern world? But for the scientists at the TIGRR Lab (Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research), the moral obligation is to reverse a human mistake. We hunted them to extinction; we owe it to them to bring them back.

Conclusion

Benjamin died alone in the cold in 1936 because humans were careless. In 2026, humans are using the most advanced technology in history to try and apologize.

Whether it works or not, one thing is certain: The line between “extinct” and “alive” is about to be erased.

Fascinated by genetic mysteries? Read about the Demon Core Incident.