If you ask a master woodcarver what their favorite wood is, there is a high chance they will whisper one name: Cherry.

It is smooth, it smells sweet when you cut it, and it holds detail better than almost any other domestic hardwood. But Cherry wood (Prunus serotina) is more than just a material for fancy tables.

It is a biological oddity. It is a tree that can kill cows, flavor rum, and—most strangely—it is a wood that changes color just by looking at the sun.

Here is the interesting story of the wood that gets a tan.

1. The “Chameleon” Effect: It Gets a Suntan

Most things fade in the sun. A red shirt turns pink; a plastic chair turns white. Cherry wood does the opposite.

When you first cut into a Cherry tree, the wood is a pale, creamy pink color. But the moment it is exposed to UV light (sunlight), a chemical reaction begins.

- The Process: The wood oxidizes rapidly. Over the course of a few months to a year, that pale pink transforms into a deep, rich reddish-brown.

- The “Bikini Line”: If you leave a coaster on a new Cherry table for a month and then move it, you will see a pale “tan line” where the wood didn’t age.

This “living finish” is why antique Cherry furniture is so prized—it literally gets more beautiful the older it gets.

2. The “Poison” Secret

While the wood is safe and the fruit is delicious, the rest of the tree is a killer.

The leaves and twigs of the Black Cherry tree contain prunasin, a compound that turns into cyanide when the leaves wilt.

- The Danger: Farmers call it a “livestock killer.” If a storm blows a branch into a pasture and the leaves start to wilt, a single cow can die from eating just a few handfuls.

- The Myth: This toxicity might be why early folklore warned against bringing Cherry branches indoors, fearing they were “Witches’ Wood.”

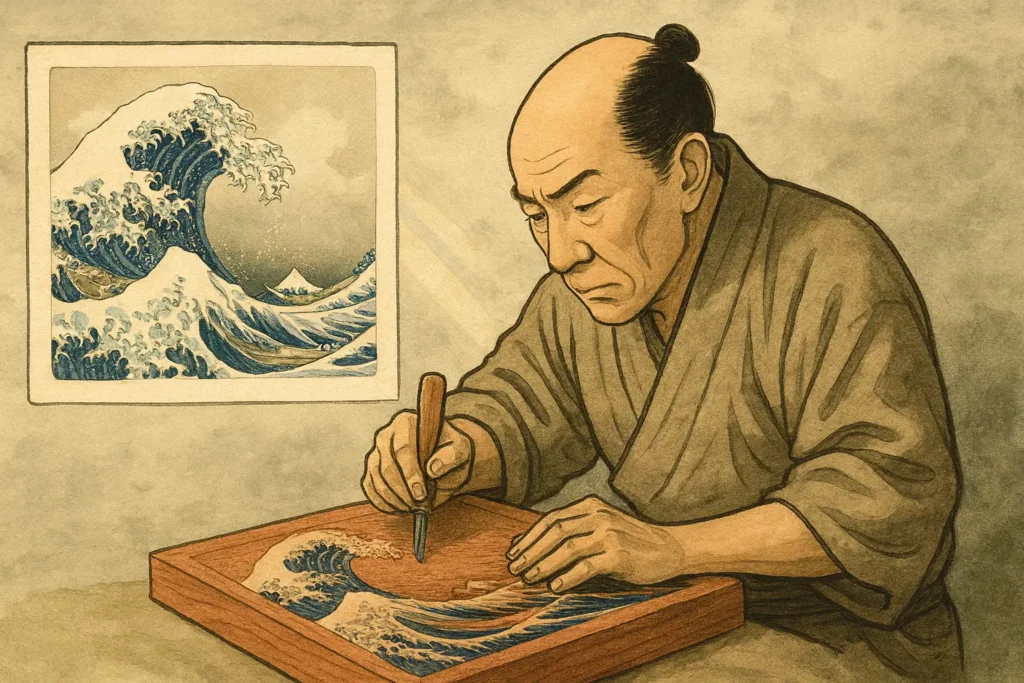

3. The Secret Behind “The Great Wave”

You know that famous Japanese image of the giant wave crashing down on boats (The Great Wave off Kanagawa by Hokusai)? You can thank Cherry wood for that.

In the Edo period of Japan, the art of Ukiyo-e (woodblock printing) relied entirely on wood that was hard enough to hold microscopic details but soft enough to carve without chipping.

They chose Wild Cherry. Every single thin line of rain, every strand of hair on a geisha, and every foam tip of the Great Wave was originally carved into a block of Cherry wood. Because the grain is so dense and uniform, it allowed artists to print thousands of copies without the block wearing down.

4. The “Rum Cherry” of the Pioneers

When European settlers arrived in North America, they didn’t just see furniture; they saw a liquor store.

They nicknamed the tree the “Rum Cherry.” They would take the small, bitter black cherries, pack them into jars, and drown them in rum and sugar. After burying the jars for a few months, the resulting “Cherry Bounce” was a popular (and potent) colonial drink.

They also used the inner bark to make cough syrup—a tradition that lives on in the “Cherry” flavor of modern medicine (though real cherry bark tastes much more bitter).

5. A Carver’s Dream (And Nightmare)

For a woodcarver, Cherry is known as “The Goldilocks Wood.”

- Not too hard: It won’t dull your tools as fast as Oak.

- Not too soft: It won’t crumble like Pine.

- The Burn: However, it has one major flaw. If you use power tools (like a Dremel or a table saw), Cherry wood burns instantly. The friction heats up the natural sugars and oils in the wood, leaving ugly black scorch marks and a smell that—while sweet—means you just ruined your piece.

Conclusion

Cherry is a wood with a personality. It demands sharp tools, it reacts to sunlight, and it has a history that spans from poisonous pastures to masterpieces of Japanese art.

So, the next time you see a dark red Cherry cabinet, remember: it didn’t start that color. It earned it.

Love the hidden stories of nature? Read about the Dynamite Tree or check out our Art & Literature tag for more creative history.

One Comment on “Cherry Wood Facts: The Wood That Gets a Suntan”